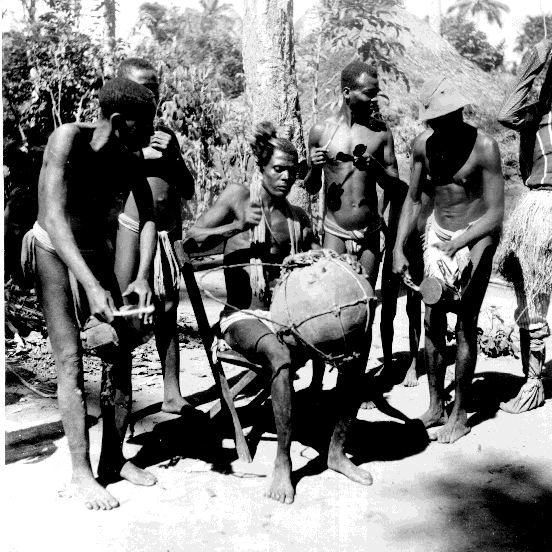

udu (pot-drum), 1925–1990

Origin: Nigeria

http://collection.spencerart.ku.edu

As I walked through one of my first festivals almost 20 years ago, I first heard the special sounds of an udu drum. Those sounds instantly found my attention, low liquid like percussion, as if calling me from a distant memory of the past. The attraction led me like moth to flame and led me into this amazing journey, and was a vital influence on my passion for indigenous instruments.

I slowly made my way toward those sounds of the udu. Under a tent over looking a beautiful Appalachian valley, a man was playing what looked to be a simple clay pot. As I drew closer to the man playing this unique instrument, I realized it was more than a clay jug. This piece of clay was built for percussion, with a side hole and textured patterns on the sides. These additions were easily recognized as parts of the instrument as it was played.

That simple, yet complex, clay pot produced the most fascinating sounds that I could imagine at the time. I was young, and only barely entrained by the indigenous instrument path. With only a djembe in my collection, I barely knew my instrument addiction. I vowed to find or make one of these wonderful drums in the future.

What is an udu drum?

Udu

Maker:Frank Giorgini (American, 1947–)

Date: 20th century

The udu is a clay pot drum with it’s origins found in Africa. There are other similar clay pot drums found in other regions such as India such as the Ghatam drum. These drums can be traced back to Nigeria and the indigenous Igbo people of that region.

Udu’s are clay vessels and traditionally have distinctive bulbous vase like bottoms with thin necks, along with the a side hole and sometimes textured decorative patterns. The circular side holes are used when playing and are key to producing the unique sounds.

These unique instruments are part idiophone and also part aerophone, but not membranophone (with no stretched skin or membrane which produces sound). mimicking sounds similar to talking drums or tablas, these sounds can be similar to watery bursts and sharp percussive tones.

What are the traditional customs for udu drum?

The Igbo people of Nigeria traditionally call all pots udu, their native language has no unique name for the clay drum itself. In the past the udu drum was exclusively used for women’s rites and ceremonies. Considering women are the keepers of pottery, this tradition seems like a logical choice. So traditionally only women were allowed to play these beautiful instruments, since they were more connected to the technology of pottery. This simple combination of Earth (clay), water, fire, and air has produced this traditional instrument, and we can probably thank women for that discovery.

These drums can be found in almost all homes in the Igbo populated regions. When not being played they may be found being used as containers for water, store grain, or even being homes to bee colonies. Within the last century udu have also been included in church music, again pointing toward the sacred perspective of the drums in the area.

The Igbo people have a traditional concept that the sounds produced from the udu are the sounds of their ancestors. With ancestor worship a important aspect of their culture, this again provides evidence of the sacred placement of the udu for the Igbo people. Making the association of udus sounds with ancestors is a integral perspective for the Igbo people, and has kept this wonderful instrument sacred throughout history and into the present.

How are udu drums made?

All these pottery methods could have full articles written on each one, and there are many places online you can find for each. Please do your own research into each method before trying making your own udu.

Making an udu drum is as simple, and as complex, as making just about any vase like vessel of clay. Traditionally Igbo women would use clay coiling methods to slowly build the vessel from the bottom up. These women would make snake like coils and wrap them around to produce the shape, then smooth out the coils and merge them into one large piece. After forming, they remove the circular side hole and add any texturing or decoration.

Contemporary artist may produce udus with the coil method, but they may also use other methods such as throwing on a pottery wheel, or using liquid slip in molds. There are many contemporary artist making udus throughout the world, which you can find a wide assortment of styles and methods for making these drums.

Once the form is made and dried, then you must fire the clay at high heat to turn it into pottery. This can be traditional pit firing methods or using a kiln or raku firing. Before firing the non heat treated clay doesn’t produce enough resonance for consideration of being called an instrument. Once the clay is fired at high heat the resonance increases dramatically, and the bright tones along with the low watery bubbling sounds unique to the udu are ready to be made.

Where can you find udu drums?

You can find udu drums all over the internet. Frank Giorgini who runs udu.com is a well known contemporary udu drum maker, with pieces that can be found in museums. There are also many fair priced udus on the internet as well, on sites such as etsy and ebay, but also from larger instrument manufacturers such as LP (which produce a line developer by Frank Giorgini but are slip and mold produced).

http://www.udu.com/

Udu Workshops Available!

Archaic Roots offers personal udu making workshops at our location in the Southern Appalachian mountains of Northeastern Georgia. We also plan on offering one public workshop each year in the fall starting in 2019. Feel free to reach out to schedule your personal workshop or ask about the fall udu workshop!

References:

- http://www.udu.com/Udu_html/uduhis.html

- K. Nicklin, “ The Ibibio musical pot,” African Arts 7(1 ), 50–55, 92 (1973). https://doi.org/10.2307/3334752 , Google ScholarCrossref

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503261

- http://www.drumdojo.com/j15/india/udu-or-ghatam-pot-drum.htm

- F. Giorgini, “ Udu Drum, Voice of the Ancestors,” Exp. Musical Inst. 5(Feb.), 7–11 (1990). , Google Scholar

- C. Achebe, Things Fall Apart, 1st Anchor Books ed. (Anchor, New York, 1994), p. 6. Google Scholar

- https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b12d/82d8301fc2bd168ed92807b2a88ab92537b5.pdf

- http://collection.spencerart.ku.edu/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=41910